When it falls incessantly and is accompanied by a bitingly cold and cruel wind that makes visibility impossible, snow provides a splendid sense of peace and tranquil charm.

At least, kinda, sorta.

When in the hands of the brilliant Robert Frost, snow is afforded that sense of beauty that is well deserved. Blankets of splendor do provide a sense of awe, after all, and when you get into blizzard territory, which is what we had in my beloved neck of the woods Sunday night into Monday, the first course of action is to concede victory for nature.

After that, you shovel, you snow-blow, you scrape, you lift, you push, you pile, you throw, you toss. Then you rest for two or three hours and do it all again.

We’re not talking a “dust of snow from a hemlock tree,” as Frost wrote so eloquently in his poem Dust of Snow. No, sir. When 20 inches of fresh snow piles on top of the foot of previous snow that refused to leave, you have walls of the stuff that make average life – you know, the commuting, the work, the appointments – very difficult.

By this point, trust me, snow has lost its peace and tranquil appeal, for sure. Not to mention how it has played havoc with your back, sent you rushing to the couch to thaw out, and disrupted your routine. All of which segues into the fact that what also piled up during those hours of work were an abudance of thoughts.

No story, mind you. But lots of thoughts. Thus, what appears this week is a full round of musings, not just the front nine.

Onward we go.

1 – It should fall on deaf ears

Complaining about a par-3 stretched to 275 yards – as PGA Tour lads did last week at the Genesis Invitational at Riviera – likely doesn’t elicit a lot of sympathy for them. After all, these are guys who routinely look at 275 yards as green-light time for second shots into par-5s. And don’t they have their fair share of 6- and 7-irons into par-5s and 445-yard par-4s where they hit driver, wedge? Yes they do. When all the numbers were crunched after four rounds, the par-3 fourth was just one of five holes at Riv that played to a field average of over par, by the slightest of margins (0.02). First-world problems, indeed.

2 – Tough to figure him out

If it was ever Jon Rahm’s intention to let his stock disintegrate and pretty much get everyone disgusted with him, my guess is he’s achieved his goal. Like, who hasn’t he bothered? When he sold his soul to play LIV Golf, what came with hundreds of millions of dollars was the knowledge that he was ineligible for the Ryder Cup. He accepted the terms but was then provided a loophole. Keep your LIV money, just pay a fine and you can get a locker with Team Europe. Others did just that. But not Jon, who has worn out so many people with his “Woe is me” routine.

3 – Jeeno does her share

World No. 1 Jeeno Thitikul holding on to win by one in her homeland, Thailand, providing her mother a rare chance to see her play, was pretty good stuff for the LPGA.

4 – Not so, Nelly

World No. 2 Nelly Korda sitting out a three-tournament swing to Asia is not good stuff for the LPGA. Apparently she hasn’t received the memo about “growing the game.”

5 – Tough to follow along

The LPGA is a curious landscape on other fronts these days. Michelle Wie West is being billed as “unretired” because she’s playing some indoor stuff with WTGL. Lexi Thompson is seen as “retired” even though she played in 14 LPGA tournaments in 2025.

6 – You’re kidding, stuffed animals?

If the over-under is one for how many Team Canada hockey players kept their Tina the Stoat stuffed animal, may I suggest you bet the under. My guess is, the trash bin that was outside the Team Canada locker room was jammed filled with those ridiculous toys given them by after losing, 2-1, in overtime in the Gold Medal game. “Here’s your silver medal, lads, and let Tina the Stoat be a token reminder of your lovely experience in Milan.”

7 – Call it as it was, silly

Good gracious, which IOC official thought handing out stuffed animals to professional athletes – especially when they are bloodied and beaten – was a good idea? Token gifts that you’d give to kids at Valentine’s Day have no place at an athletic gala like an Olympic Gold Medal game.

8 – Frost delay in effect

Just looked out my window. We could be playing simulator golf till June.

9 – Not exactly news

With this week’s Cognizant Classic in The Palm Beaches devoid of many of the world’s top-ranked players, there are dispatches being published about a clear divide. Tournaments that get the big names, and those that don’t. Really? It’s been that way for many years now, so where is the “news” in that?

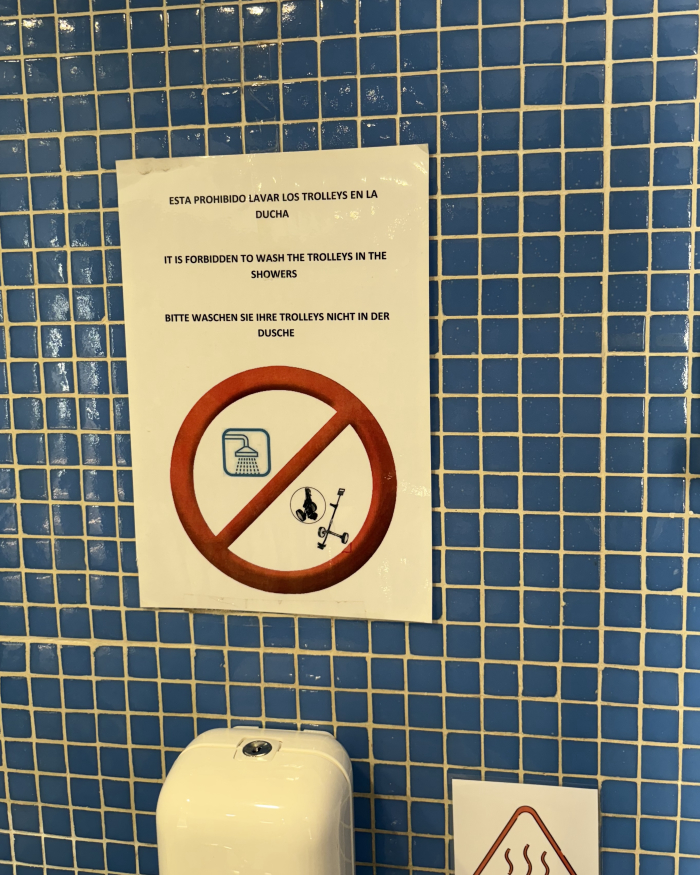

GOLF COURSE PHOTO -- If you find yourself at Lauro GC near Malaga, Spain, don't even think about bringing your pushcart into the men's room to get it washed up and cleaned off. Strictly forbidden. The photo is courtesy of Dan Crane. As always, should you have a clever golf course sign that you run across, please send it to jim@powerfades.com and we'll share it with readers.

10 – Here’s a warm thought

Six weeks from tomorrow, Round 1 of the Masters will be played. Start your Pimento.

11 – The name is familiar

Honestly, this is no disrespect to the latest PGA Tour winner, Cameron Bridgeman. But with a nod to many years lived in other eras, when I hear the name Bridgeman, I think Junior Bridgeman first and foremost. (He authored a wonderful life, Junior Bridgeman did.)

12 – Stop your gloating

He who laughs last on the tee box probably hit first and had a favorable wind.

13 – How do you close the door?

There are two types of people in this world – those who attend pro golf tournaments and let the port-o-john doors slam and those who close them gently. Proudly, I am part of the gentle-close citizenry.

14 – Still, I will laugh

Which reminds me of one of my favorite stories from years of watching pro golf tournaments and befriending security officials and very astute marshals. The story has its roots in a Texas tournament, the Nelson, I believe, and one of the security officers noticed that a well-dressed woman near the green kept standing, then sitting. Stand, sit. Stand, sit. He investigated and discovered that the polite woman took the green marshal literally when he bellowed out as a players prepared to putt, “Stand, please.” So she did.

15 – Great partnerships

When conversations turn to which teams you would like to see play in the annual Zurich Classic of New Orleans, I abstain. But it does get my mind wandering. Forget golfers; mention great partnerships and promptly my mind centers on Mark Knopfler and Emmylou Harris, garlic and capers, a beach chair and book.

16 – Can’t break the habit

In all due respect to my friends who sell corporate sponsorships and are involved in marketing events with ever-changing title names, when it comes to discussing the PGA Tour we speak shorthand. You’re playing “the Honda,” last week was “Riv,” a favorite is “the Nelson,” everyone loves “the Crosby,” they still play “Greater Hartford,” and who do you like at “Hilton Head.” Editors don’t let that get into the stories, mind you. But it’s in our vernacular.

17 – Riveting, eh?

Overseeded rye. In case you’re looking for a topic that will empty the dinner table quickly tonight.

18 – Move it along

Remember, ready golf is proper golf, and whomever is ready hits first.